Indie eBooks or ePulps?

Indie-publishing may be a very different beast than most people give it credit for. Its readership and

reader expectations differ significantly from those of traditional

publishing. It might pay to view ebooks, and especially indie-publishing, not as the 21st century version of traditional book publishing, but as the 21st century version of the fiction magazine – the

“pulps” of the past. If this is the case, then ebooks may not be the future of book publishing, but rather, destined to remain a

semi-autonomous niche market. Far fetched? Let's look at the many parallels

between the pulps and indie-publishing so that you can decide for

yourself.

The pulp magazines

of the first half of the last century were "cheap reads," like the indie-published ebooks

today. In the pulp era, when hardcover books cost

between $2 to $3, with the cheaper reprints at a $1, most pulp

magazines sold for $.10 to $.20. Today, with hardcover books' cover

price in the $20 to $30 range, and traditionally published ebooks

running $12 to $16, most indie-published ebooks cost between $1 and

$5; priced just like the pulps when compared to traditionally published books, and aimed at same, budget conscious readers. The similarities, however, go much deeper than just price.

Like the pulps,

indie-published ebooks appeal to avid readers – readers who consume

stories faster than traditional publishers release them. Just as the

pulps met the demand for more stories, more often, indie-published

books, released by the thousands each week, supplement the

traditional publishers' slower release cycle.

And like the pulps, indie-publishing, with it's low overhead and cheap, ebook

format, can profitably serve niche markets; markets too small, or too

controversial, for traditional publishers to bother with. In addition, many indie-authors, like pulp publishers, often make slim profits on each issue, but enough to keep cranking out titles year after year.

The similarities

extend beyond price, volume, and profits. It's reflected in

content as well. As I mentioned above, the pulps offered stories for

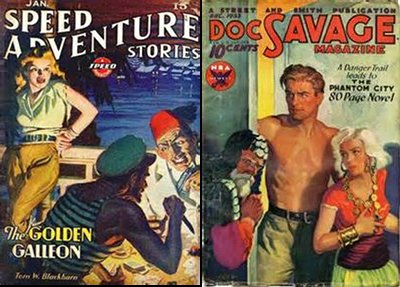

every reader, every interest and taste. There were pulp magazines

devoted to railroads, air planes, submarines, zeppelins, ships and

the sea, cowboys, detectives, gangsters, science fiction, fantasy,

horror, boxing, sports, and all types of romance stories.

Indie-published ebooks offer the same sweeping spectrum of stories for every taste, no matter how obscure.

The distribution

model of pulps and ebooks also share the distinction that, unlike

traditionally published books, you're not likely to find them in

bookstores. The pulps were sold on newsstands, in drug stores, and in

other non-traditional book venues. Today indie-ebooks, POD print

books, and audio books are mostly sold online, rarely finding their

way into bookstores.

Indie-ebooks and

pulps share more than just a similar market. Their subject

matter, writing styles, and writing philosophy are very similar as

well. Of course there is a wide variety of small press and

indie-published books, many of which don't follow the pulp formula,

yet it seems that many of the most successful ones do. Readers of

both the pulps, and indie-published ebooks, tend to be story

orientated readers rather than style orientated ones. The great

secret in publishing is that many readers are not all that fussy when

it comes to how stories are written. If the story draws them in, and

they find it entertaining, they'll turn a blind eye to how well it's

written. “Pot boilers” have always sold well.

Moreover, not only do readers value stories more than writing, they

like the familiar. Stories written in familiar formulas are welcomed,

rather than despised. Much of the advice given to aspiring

indie-writers promote the pulp, formula of writing. Give them stories

you know they like – research your market. Write fast, one draft if

you can. Write short, 50K word novels, short novellas, and short

stories. Publish frequently to keep readers engaged. Find a formula

that works and stick with it. And write series, where not only the

formula, but the characters are familiar. I'm not saying that this

style is universal in indie-writing, only that it makes up a good

portion of the commercially successful indie-ebooks exactly because

it appeals to the same type of reader that was attracted to the pulps

in their day.

Some pulp writers, like indie-writers, found great commercially success, despite the fact that neither the pulps or indies stories are reviewed in the mainstream media. In the hay day of

pulps, there were pulp writers making movie star incomes, just as

there are millionaire indie-writers today. And, like today's

indie-authors, many new writers wrote for the pulps before moving on (or “up”) to traditional publishing – just like the

many successful indie-writers do today. Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice

Burroughs, P G Wodehouse, Raymond Chandler, Ray Bradbury, and H P

Lovecraft, just to name a few started their careers writing for the

pulps. Like their modern counterparts, pulp writers sold their work in many formats from traditional books to Hollywood screen plays, like

today's hybrid writers and indie-writers who diversify

into POD books and audio books. The first

Tarzan movie came out only a few years after it appeared in the

pulps, like The Martian today. This entrepreneur spirit, is a feature of both the successful

pulp and indie author

.

There are, of

course, many differences as well. Pulp writers, for example, wrote

for a much smaller audience – pulp magazine editors. The magazines

offered an established brand and provided services like editing and

story guidance, ideas, proofreading, and marketing at no charge to

the writer. The magazines, being anthologies, helped new writers

reach readers and convey credibility by their association with both

the magazine and its more well known contributors. These days,

indie-authors must pay for many of these services out of pockets–

and bear the financial risks involved in publishing as well.

Despite the

differences, it seems to me that the indie-publisher today is the

direct descendant of pulp writers of the past. And that their markets

are functionally the same. If that is the case, then the

indie-published ebook market should be viewed as something distinct

and different from the tradition print book market – not only in

form, but in function as well.

So what?

Well, for the

indie-writer it may mean looking at their business a bit differently,

since it's a different tradition with, perhaps, a different future than traditional book publishing. Traditional book publishers might

want to take a hard look at their position in that market with a

historical perspective. They co-existed with, and survived long after

the pulp market died off. They may not be able to outlive the

indie-ebook market, but they can almost certainly co-exist with it.

The question then

arises, do they need to compete in the ebook market at all? They

left the pulps be pulps, so could they not turn a blind eye on ebook

publishing as well? Given that they make something like 1/3rd of their

incomes comes from ebooks, the answer might be a “No!” – if it

meant abandoning that income entirely. But does it? If a publisher

has a stable of proven, popular authors, wouldn't these authors draw

most of their readers back to the print, if that was their only

option (at least on first release)? How many ebook customers of

traditionally published ebooks are entirely committed to reading

ebooks and only ebooks? Is there not still time to draw a line

between “books” in paper, and indie-published ebooks or in

effect,“ePulps”?

Given that the

(discounted) price of the paper edition is not much more than the

agency ebook price, any resistance to this change would likely arise

only from the format rather than price. I would argue that as of

today, that risk seems modest. So, with the modest risk of leaving a

few customers behind, traditional book publishers would create the

opportunity of redefining both ebooks and print books. By exiting the

ebook market, at least for hardcover and trade paperbacks, they could

then draw a bold line in the sand. They could then make the case

(rightly or wrongly) that there is a clear distinction between

“real,” traditionally published authors, who write “real”

books that are carefully selected and edited for a quality reading

experience, vs the non-curated indie-published, “ePulps”, rejected stories written

by beginners and amateurs, and published in great numbers on the cheap.

And by removing their hardcover and trade paperback library from

their ebook offering, they would drive business back into the

business they know best – paper publishing.

Still, they need not

abandon the ebook market entirely. They could release the ebook

versions of their “real” books a month or two after the book's

mass market paperback release, priced competitively with indie

ebooks, say $5.99 or less. In this way they would eventually reach

every potential customer; from the eager hardcover buyer to the

budget reader willing to wait for the cheap ebook, without diluting

the idea that traditionally published books are fundamentally

different from indie-published “ePulps.”

While I'm playing

the devil's advocate here as far as what traditional publishers might

think and do in the ebook market, I feel comparing indie-publishing

to pulps is valid. A lot of people think the big five publishers are shooting

themselves in the foot with their high prices for ebooks, but they may just be too timid. Yes, the higher prices set them apart

from the indies, but by withdrawing their newest, most in-demand

books, they might make that distinction even sharper. In the past

there was a distinction between “pulp writers” and “paperback

writers” and published authors of "books." Fair or not, they could make that

distinction again, and reinforce it by keeping their authors out of

the indie-writers' ebook market, and perhaps secure a mindset for

their paper books for many decades to come.

There are many

people who say that ebooks are the books of the future, and if

traditional publishers don't embrace change, they are doomed for

irrelevance down the road. I'm old enough to know, that, even if they

are right, it's unlikely happen before we're all driving flying cars.

And when you consider that cassettes, eight-track, CDs, itunes, and

streaming music services haven't managed to push vinyl records into

the dumpster of history (They're Back!), I have to believe that paper

books have a long, long future ahead of them no matter what. Indeed,

since ebooks are dependent on digital technology, which changes very

rapidly, I'd say that one should wonder more about the staying power

of ebooks than that of paper books.

For information on

the pulps I consulted The Pulps, Fifty Years of American Pop

Culture, edited by Tony Goodstone, researched consultant: Sam

Moskowitz