|

| source: https://www.seanpcarlin.com/the-writers-journey/ |

A few posts ago I began to discuss how I and other writers construct stories. However I got sidetracked and never got around to the “other writers'” approach to storytelling. Here’s that second part of the discussion.

Many writers take a systematic approach to writing stories, not only outlining their story before they begin to write it, but think of the story as a word-structure to build. And they use a blueprint to construct their stories. So let’s look at a few of those blueprints.

The first one is the classic “Hero’s Journey” as described by Joseph Campbell.

In the illustration above, we see a graphic representation of the story structure. In its most simplest form, the hero is called to some sort of adventure. This leads the hero into unexplored territory, where they encounter many tribulations, until they reach a point where it’s either do or die, and in doing, become better people, returning home transformed. The basic idea, which will be repeated in the following blueprints is that the hero leaves their old lives, faces a test of fire, and comes out better for it. (Or not, if one wishes to make a tragedy.)

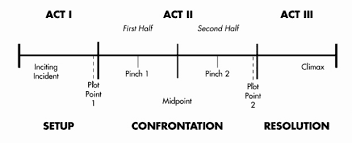

The next most common blueprint is the three act structure, as pictured below.

|

| source: https://allthetropes.org/wiki/Three-Act_Structure |

The three-act structure dates back to the Greeks and is widely used in plays and screenplays as well as books

The Setup is the opening act. The main character and setting are introduced. This act includes the inciting incident that gets the hero to act on something that leads to the second act.

The second act, the Confrontation, involves a series of increasingly complex challenges that lead to the final, high stakes reckoning that drives the story it its third act, the Resolution, along with the events that follow from the climax, the falling action and denouement, as shown in the graphic above.

James Scott Bell describes this structure as beginning with a disturbance that upends the protagonist’s ordinary life. The protagonist then goes through the one-way doorway one, to the middle of the story with no way back. Ahead is doorway two, which leads to the final resolution of the disturbance, again, with no way back.

|

| https://www.critiquecircle.com/blog.asp?blogID=280 |

And then there is the Seven Points structure. It begins with a Hook or Inciting Incident, the story’s starting point. Then Plot Turn 1 or Plot Point 1 , which introduces the conflict that moves the story. This is followed by Pinch Point 1, when the protagonist faces increasing resistance to achieving his or her goals. At the Midpoint, the protagonist responds to this resistance with action. However, then comes Pinch Point 2, where the protagonist faces increased resistance. This leads to Plot Turn 2 or Plot Point 2, which is like the break from act two to act three – the protagonist acts to achieve his or her goals at the climax, which leads to the Resolution – the conflict resolved, the characters changed as a result of their experiences.

There are several more approaches to story telling. The blueprints can get a lot more detailed. One of the most famous one is by Lester Dent, who wrote most of the Doc Savage stories. He had a master plot planned out for a 6,000 word story divided into four 1,500 word sections in which he details what the writer should consider and happen in each section. The complete outline can be found here: https://www.paper-dragon.com/1939/dent.html

A somewhat expanded version of this, originally conceived for screen plays is Blake Snyder’s “Save the Cat!” beat sheet, but is used by novelist as well. It outlines a three act structure down to word count.

In this structure, the first act, represents 25% of the total word count, the second act, 50%, and the third, 25% of the total word count. You then divide these acts into scenes that run between 1,000 and 2,000 words each.

After that, he breaks the story down into 15 story beats, and goes into detail about the relative number of scenes each of these story beats should contain. Act one includes the Opening Image and Theme Stated, Catalyst and Debate and the Break into (Act) Two, where the protagonist decides to accept the call to adventure. Act two starts with the introduction of new characters, the B Story, and then Fun and Games, where the protagonist finds themselves in the new world, either loving it or hating it. At the Midpoint, the protagonist experiences either a false victory or defeat – a game changing plot twist, and the ante is upped significantly. This is followed at the midpoint of the story by the Bad Guys Close In, things get hotter. At about the ¾ mark of the story we get to All is Lost, which in one scene the protagonist is at their lowest point. This is followed by Dark Night of the Soul, where the protagonist reviews what has happened, and learns from it. The Break into (Act) Three is the single scene where the protagonist realizes what he or she must do to save the situation, and change as well. Act three is the Finale, where the protagonist acts on the plan he or she has come up with, Gathers the Team, Executes the Plan, only to face a new twist in the High Tower Surprise that presents an unexpected challenge, and Digs Deep Down to overcome it by Execution of New Plan that either succeeds or fails, depending on what outcome you want. This is followed by a Final Image, the “And they lived…. Or not” scene.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with any of these approaches. I don't use them, in part because I'm not very detail orientated. I simply don't think stories as needing to be "constructed." Apparently, I didn’t inherit my engineer father’s mindset. Instead, I live with the story in my head, and when I know the story, as if I had lived it, I sit down and tell it. That, at least, is the ideal. The reality is I often start a story these days before I’ve completely daydreamed the story up, and then have to pause my writing until I’ve dreamed up the rest of the story.

No comments:

Post a Comment